It’s raining in Far West Dallas, hard enough for rivulets of water to ooze through cheap, wooden window and door frames and down the water-stained walls of housing projects clumped together along and to the west of Interstate 30.

People living along posh residential streets welcomed the precipitation, which kept their well-manicured lawns lush and green, but, in West Dallas – known as “The Devil’s Back Door”– dirt streets turned into mud bogs, nearly impossible to traverse on foot and equally difficult in cars and trucks.

Aside from impassable streets, West Dallas residents also were unknowing victims of the daily doses of lead emissions from nearby refining smelters. Because few residents could afford the luxury of air conditioning, doors and windows were kept open during the summer to combat the heat, which directly exposed families to the toxins spewing from the smelters.

Years ago, the rickety rows of housing projects in West Dallas were christened with deceptively idyllic names: La Loma, Buena Vista, La Bajada and Ledbetter Gardens. Residents rarely wandered too far from their homes; most trips were on foot, with regular routes confined to school, to get food and to one of the nearby Catholic churches. West Dallas families, mostly headed by blue collar and domestic workers, had been priced out of everywhere else in Big D and were therefore herded into the low-cost housing beyond the smokestacks and industrial parks, in neighborhoods such as Greenleaf Village, Muncie and the Fish Trap.

The West Dallas projects, hastily constructed in 1954, were divided into three separate developments segregated by skin color – Black, brown and white – all poor and with little hope of escape. In nice weather, these neighborhoods quivered with lively Spanish-language conversations, the laughter of African American women hanging laundry to dry and children playing in the streets.

There were no grocery stores in Far West Dallas, so residents relied on bodegas for each meal’s groceries. Without refrigerators, it was impossible to keep essentials cold, so trips to the convenience store were necessary before every meal.

David Medina, born in 1955 at Parkland, Dallas’ charity hospital, remembers the two-bedroom bungalow of his childhood: “We had no indoor plumbing, no air conditioning or heat and thin, bare plywood floors.”

The remainder of this article is reserved for subscribers only

In addition to receiving all of our quarterly magazines by mail, subscribers to Southern Calls have exclusive access to additional online articles, as well as ability to read all Southern Calls magazine articles as they come available.

Get your One Year or Two Year subscription today, or login here to continue viewing the rest of the article.

Order this issue

Southern Calls Issue 33

In stock

Articles Relating to Issue 33

Cremation in America

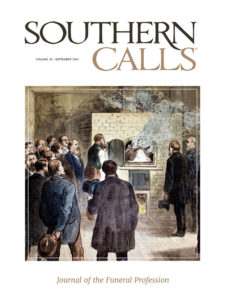

America’s “Modern” Cremation Movement It was a cold and rainy December day in 1876 when the modern cremation movement in America made its debut. In the small town of Washington, Penn., Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne, a local eccentric physician, had built a simple…

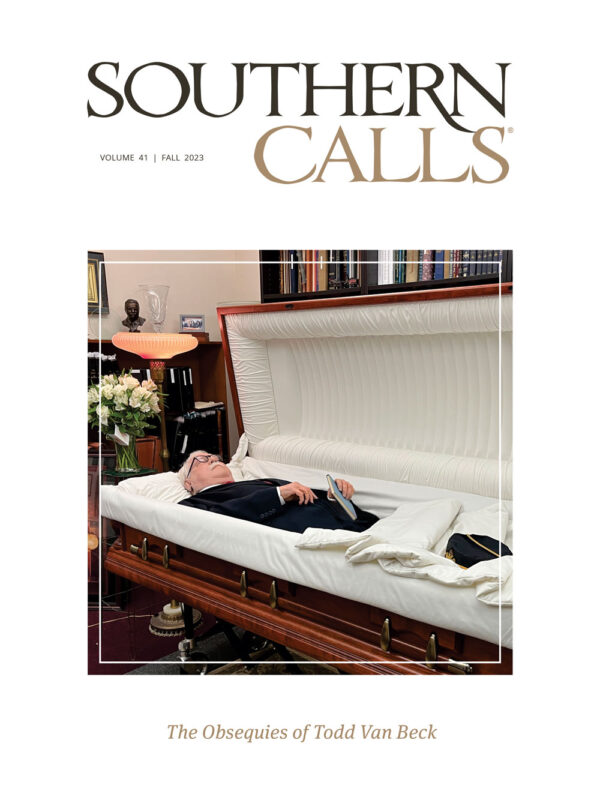

S. Todd Rose

As chief of the Air Force’s Casualty Headquarters, Todd Rose is charged with a mission unlike any other in the United States Air Force. When an airman is killed, wounded, injured, or even takes ill, it is Todd’s job is to ensure actions are taken to support the airman…

Issue 33 Available Now

It’s already September, the leaves will be changing soon, and the next issue of Southern Calls will be arriving in your mailbox! There’s a lot to look forward to… first, we have chief of the Air Force’s Casualty Headquarters, S. Todd Rose, with a thoughtful story of…